The Truth About Food Dyes and ADHD: What Science Tell Us

Research suggests that synthetic food coloring affects ADHD symptoms in some children. Here, an expert answers common questions, recounts research about food dyes, and gives strategies for removing them from your child’s diet.

Editor’s Note: On January 15, 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the use of red dye No. 3 in food and ingested drugs, which has been linked to cancer. Food manufacturers will have until January 2027 to remove red dye No. 3, and drug makers will have until January 2028.

April 22, 2020

Irritability. Extreme hyperactivity. Explosive anger. Anxiety, or even despondency. If you’ve noticed a spike in undesirable emotions and behaviors after your child eats a bowl of Fruit Loops or a handful of M&Ms — and suspected a link between their ADHD symptoms and diet — you are not alone.

With growing frequency, parents are noting a connection between their children’s behavior and their consumption of food containing synthetic dyes — namely, red #3, red #40, and yellow #5. In a 2016 report, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), a consumer advocacy group, said more than 2,000 parents had reported concerns with their kids’ consumption of food dyes. “We’re a non-profit organization and somehow people manage to find us,” says Lisa Lefferts, MSPH, a senior scientist with CSPI, which has petitioned the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ban these food dyes. “The stories are heartbreaking.”

Joining the CSPI in its crusade is the American Academy of Pediatrics1 and ADHD experts like Joel Nigg, Ph.D., director of the ADHD Research Program at Oregon Health and Science University. Nigg and many of his colleagues in science are calling on the FDA to either ban food dyes completely or require a warning label about their effects on hyperactivity to increase awareness.2

Is It Time to Ban Food Dyes?

Based on research, including Nigg’s own review of the literature in 2012, restricting the consumption of synthetic food dyes does benefit some children with ADHD.3 Although aggregate effects are quite small, food dyes affect some children more than others. Overall, they appear to affect only a minority of children with ADHD, but this still represents tens of thousands of children or more in the U.S.

Similar studies were enough to convince the United Kingdom and the European Union, beginning in 2008, to require warning labels on food containing food dyes. Some manufacturers like McDonald’s, Mars, Haribou, and Kellogg removed synthetic food dyes from their products in the United Kingdom in the years that followed, with a few (like Nestlé and Kraft) following suit in the U.S.

Nigg and the others are now encouraging similar action from the FDA, which has reviewed the research several times since 2011 and decided to take limited action on food dyes.4 (Read the FDA’s “Final Rules: Food Additives and Color Additives” here.) In 2016, CSPI sent a detailed report with updated research, a letter signed by 13 scientists, and submitted further legal arguments for a warning label to be added to foods containing dyes.” (Click here to read the report, “Seeing Red”.)

In October 2022, CSPI and 23 other organizations and scientists again petitioned the FDA to formally remove Red 3 from the list of approved color additives in foods, dietary supplements, and oral medicines. The FDA has failed to act, but it began facing increased pressure when the state of California passed AB-418, the California Food Safety Act of 2023, which bans Red 3 and three other food additives.

To help parents sort through the science on food dyes, ADDitude spoke to Nigg about research findings to date.

[The Sugar Wars: How Food Impacts ADHD Symptoms]

Q: Do food dyes exacerbate ADHD symptoms?

Dr. Nigg: In my opinion, there is enough evidence that food dyes affect behavior in some sensitive children with ADHD (and other children without the condition) to justify warning labels on foods containing synthetic dyes. The FDA considered the issue in 2011 and again briefly in 2019, but opted not to take action. Since 2011, several new literature reviews have converged supporting the conclusion that food dyes increase the risk of ADHD symptoms.

The value judgment facing policymakers and parents is this: Do we feed our children products with uncertain safety data until they are definitely proven harmful, or do we restrict products with uncertain safety data until they are proven safe? Food dyes have not been proven safe for children, and they may increase symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity. For some children, this may be one too many challenges to their nervous system.

[Download This Guide: What to Eat (and Avoid) for Improved ADHD Symptoms]

Q: Are children with ADHD more sensitive to food dyes than children without the diagnosis?

Dr. Nigg: It appears that food dyes are a “public health concern” that affects children with and without ADHD. That said, food dyes do affect some children more than others. (See “Is Your Child Sensitive to Food Dyes?” below.)

Q: Why are you, and other experts, convinced that synthetic food dyes affect behavior in children with ADHD?

Dr. Nigg: Although overall effects are small, it appears that food dyes trigger and/or worsen ADHD symptoms in some children.5 The FDA appears to acknowledge this in its 2011 findings. That is enough to warn parents and, as I’ve said, consumer groups and scientists have made this recommendation to the FDA. The FDA has, to date, concluded that the data are not definitive enough for them to act.

They point out that the individual studies are often quite weak and overall are small and dated. This is true. We lack contemporary studies in the U.S. However, I would opt for being more precautionary given these are the data we have, rather than waiting for data that may never appear.

ADHD is caused by the accumulating contributions of many small factors. Food dyes appear to be one of them. Although many children who are sensitive to food dyes are also sensitive to other elements in food, food dyes are a straightforward target. Should parents avoid food dyes? If possible, you can remove one of the many potential negative factors. For this reason, I don’t allow my son to consume synthetic food dyes.

Parents are well-advised to remove food dyes from their child’s diet if they can. It is on the list of things to try to do—along with other health actions like a healthy diet, exercise, and lower stress. I encourage parents to do what they can knowing it’s hard to do it all. Every bit can help.

In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Environmental Health sent a letter to the FDA, citing “critical weaknesses in the current food additives regulatory process, which doesn’t do enough to ensure all chemicals added to foods are safe enough to be part of a family’s diet.”

Q: What kinds of symptoms do food dyes bring about in children with and without ADHD?

Dr. Nigg: Some children may experience more aggression and hyperactivity, and reduced attention and focus.5 There is some secondary evidence of effects on irritability, but most studies did not look at this formally. Food dyes probably make children with and without ADHD more irritable. However, in most cases, ADHD is an accumulation of multiple risk factors. The effect of food dyes is more significant in a child with ADHD who is more sensitive to them.

Q: Do food dyes affect the potency or effectiveness of ADHD medication?

Dr. Nigg: This hasn’t been studied at this point.

Q: What synthetic dyes should parents look for on food labels?

Dr. Nigg: Food dyes add no nutritional value, and don’t contribute, in any way, to how food tastes. They’re put into foods marketed mostly to children — cereal, yogurt, and snacks — to make them more appealing. Currently, there are nine FDA-approved additives: Blue #1, Blue #2, Green #3, Orange B, Citrus Red #2, Red #3, Red #40, Yellow #5 and Yellow #6. In the U.S., Red #40, Yellow #5, and Yellow #6 comprise over 90 percent of the dyes used in food.

Q: What are your best strategies for eliminating food dyes from the family diet?

Dr. Nigg: Recognize that avoiding food dyes is one of several possible actions to help your child with ADHD, and you can’t do everything. But if you feel you want to try to avoid synthetic food dyes, steer clear of most processed and packaged foods. That includes beverages like soda and juices. Eat whole foods found on the perimeter of the grocery store — eggs, milk, cottage cheese, meat and poultry, nuts and seeds, fresh fruits, vegetables, and legumes.

Families should also be cautious when buying seemingly “healthy” foods, some of which contain synthetic dyes — pickles, flavored oatmeal, salad dressing, peanut butter, and microwave popcorn, for example. Synthetic dyes can also be found in toothpaste, medication, and cosmetics. Parents should read all product labels closely.

Advice from Families Who Avoid Food Dyes

Although Justin* is only 12, he’s already an expert at reading food labels. That’s because whenever he eats anything with food dye in it — especially red #40 — he becomes cranky, lethargic, and irritable for several days. He feels so badly after consuming food dyes that he works hard to avoid them. The food dyes found in candy is so problematic for Justin that his mom, Hillary, officially canceled Halloween last year. The California-based family plans to go to Disneyland from now on.

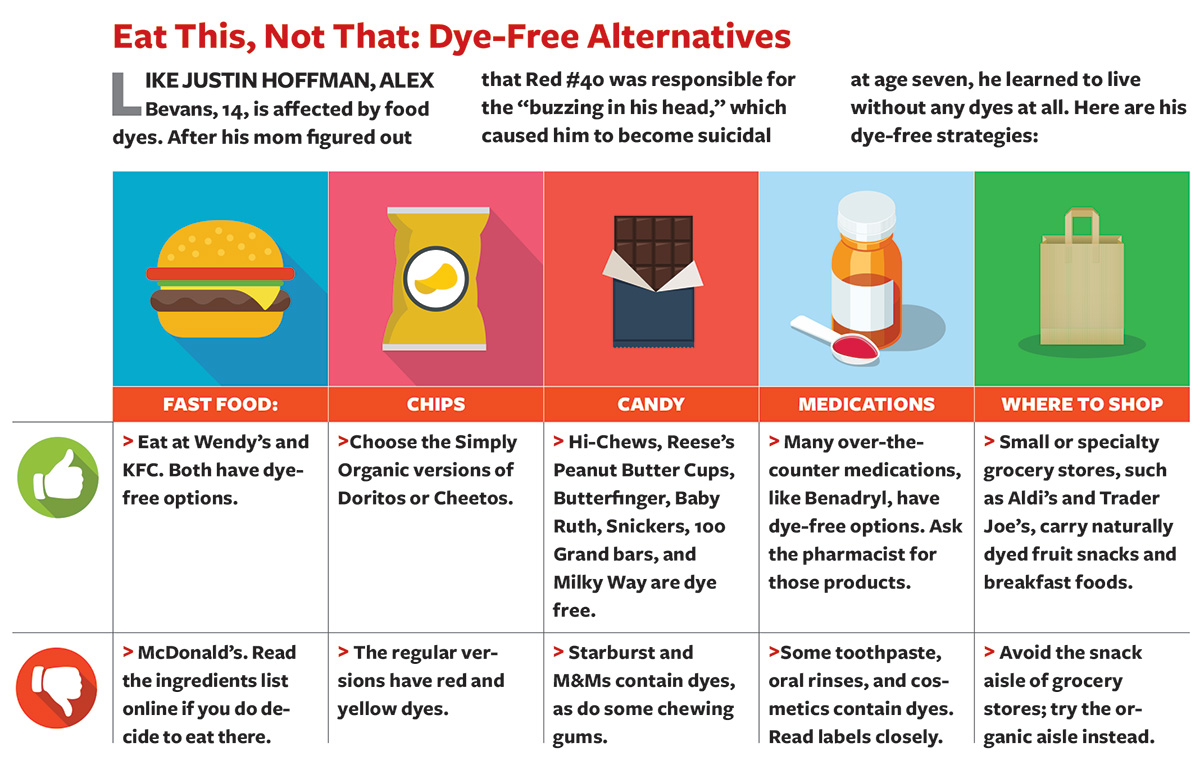

Alex Bevans, now 14, started avoiding food dyes seven years ago after scary symptoms no doctor could explain. Listed in the chart below are Alex and Justin’s favorite food-dye-free recommendations. To learn more about what the Bevans family experienced, watch mom Jessica’s TEDx Talk.

(*Name changed to protect the family’s privacy.)

Is Your Child Sensitive to Food Dyes? The 7-Step Elimination Test

Nigg says avoiding foods containing artificial dyes takes work and a family commitment for two weeks. Here’s how to do it:

Step #1. Get the entire family on board. For best results, it’s important that everyone is committed to the elimination diet. Have each family member sign a contract agreeing to avoid food containing synthetic dyes for two weeks.

Step #2. To help children adjust to losing favorite foods during this temporary period, find alternative “fun” foods — dark chocolate with no additives, for example, or plain popcorn.

Step #3. Remove all foods containing dyes from the refrigerator, pantry, and wherever food is stored.

Step #4. For two weeks, serve only food without dyes. Many companies including Kraft, Campbell Soup, Frito-Lay, General Mills, Kellogg, Chick-fil-A, Panera, Subway, and Taco Bell have dye-free versions of their products.

Step #5. Keep a detailed diary of your child’s behavior, using a checklist of the behaviors you are most concerned about. Start recording your observations two weeks before the start of the elimination diet, and continue through the end of the two-week period.

Step #6. Compare your diary notes from the pretrial and actual trial. If you see improvement in behavior, reintroduce foods one at a time for a few days to see if problems re-emerge. Or, after 14 days, reintroduce food additives into your child’s diet by squeezing a few drops of artificial food coloring (sold in grocery stores) into a glass of water, and having your child drink it. Observe her behavior for three hours. If you don’t see a change, give her a second glass and look for hyperactivity.

Step #7. Results should be easy to see. If you see only a subtle change in behavior after avoiding food dyes, it may not be worth the effort and cost to continue.

[Click To Read: 6 Essential, Natural Supplements for ADHD]

View Article Sources

1 Leonardo Trasande, Rachel M. Shaffer, Sheela Sathyanarayana, COUNCIL ON ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH, Jennifer A. Lowry, Samantha Ahdoot, Carl R. Baum, FACMT, Aaron S. Bernstein, Aparna Bole, Carla C. Campbell, Philip J. Landrigan, Susan E. Pacheco, Adam J. Spanier, Alan D. Woolf; Food Additives and Child Health. Pediatrics August 2018; 142 (2): e20181410. 10.1542/peds.2018-1410

2 Food Additive and Color Additive Petitions Under Review or Held in Abeyance; September 30, 2024; https://www.hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=FAP-CAP

3 Nigg JT, Lewis K, Edinger T, Falk M. Meta-analysis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, restriction diet, and synthetic food color additives. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;51(1):86-97.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.015. PMID: 22176942; PMCID: PMC4321798.

4 Erickson, B. (2011). FOOD DYE DEBATE RESURFACES. Chemical & Engineering News, 89, 27. https://doi.org/10.1021/CEN-V089N016.P027.

5 Vojdani, A., & Vojdani, C. (2015). Immune reactivity to food coloring.. Alternative therapies in health and medicine, 21 Suppl 1, 52-62.